Food Allergy Follies: Unpacking Immune Responses and Natural Relief

Understand your food allergy immune response. Discover causes, triggers, and effective strategies for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.

Why Does My Body Attack My Food?

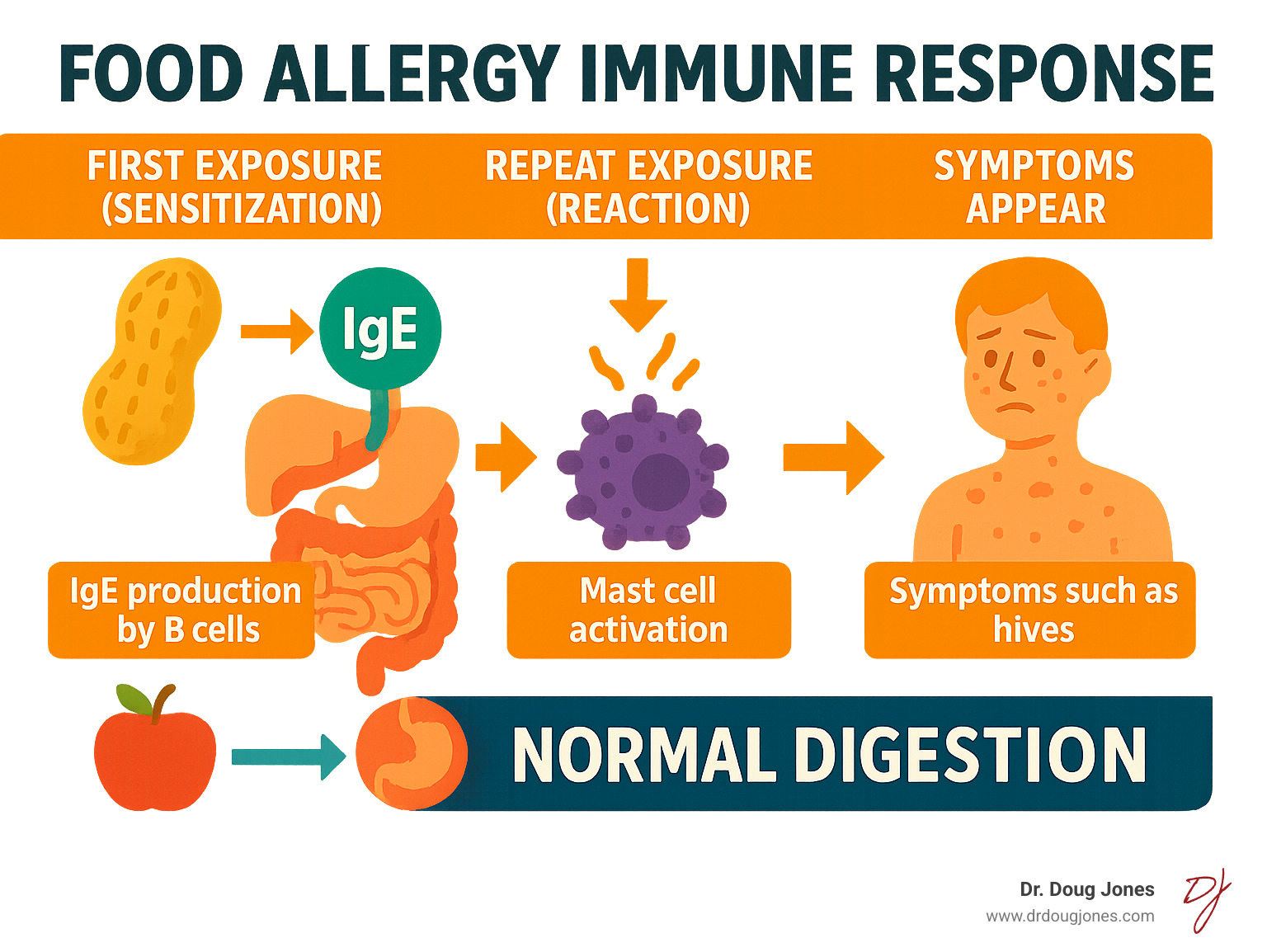

When you bite into a peanut butter sandwich and your throat starts closing, or your child breaks out in hives after a sip of milk, you're witnessing a food allergy immune response—your body's misguided attempt to protect you from what it perceives as a dangerous invader.

Quick Answer: Food Allergy Immune Response Explained

- Sensitization: Your immune system mistakenly identifies a harmless food protein as a threat and creates IgE antibodies.

- Reaction: On repeat exposure, these IgE antibodies trigger cells to release histamine and other inflammatory chemicals.

- Symptoms: Within minutes, you can experience hives, swelling, digestive upset, or even life-threatening anaphylaxis.

Food allergies affect up to 10% of children and 8% of adults in the US, with rates climbing since the late 1990s. This happens when your immune system mistakenly identifies a harmless food as a threat, launching an aggressive attack that can cause inflammation and severe symptoms.

This isn't your fault, and it's not something you can simply "get over." But understanding exactly how your immune system creates this perfect storm of chaos can be the first step toward finding real, lasting relief.

I'm Dr. Doug Jones, a board-certified immunologist. For over a decade, I've helped thousands of patients from all over the world understand and manage complex food allergy immune responses. Through my work, I've seen how a personalized approach can transform lives, from infants with severe allergies to adults with immune dysfunction.

Food Allergy vs. Food Intolerance: A Crucial Biological Distinction

Imagine one person's lips swell minutes after eating cheese, while another feels bloated hours after eating ice cream. Both are reactions to food, but one is a potentially life-threatening allergy and the other is a digestive intolerance. Understanding this distinction is crucial.

A food allergy is your immune system overreacting to something harmless. Food intolerance, on the other hand, is a digestive problem, not an immune one.

| Feature | Food Allergy | Food Intolerance |

|---|---|---|

| Immune System | Involved (IgE antibodies, immune cells) | Not involved (typically a digestive issue) |

| Onset of Symptoms | Rapid (minutes to 2 hours) | Slower (hours to days) |

| Severity | Can be severe, life-threatening (anaphylaxis) | Generally less severe, non-life-threatening |

| Amount of Food | Even microscopic amounts can trigger a reaction | Usually dose-dependent; small amounts often tolerated |

| Symptoms | Skin (hives, swelling), GI (vomiting, diarrhea), respiratory (wheezing), cardiovascular (shock) | GI (bloating, gas, diarrhea, cramps), headaches, fatigue |

| Examples | Peanut, milk, egg, shellfish allergy | Lactose intolerance, IBS, caffeine sensitivity |

The Allergic Pathway: An Immune System Overreaction

A true food allergy is an IgE-mediated response. During a first exposure (sensitization), your immune system creates IgE antibodies specific to a food protein. These antibodies attach to mast cells and basophils, which are immune cells concentrated in your skin, airways, and gut.

On repeat exposure, the food protein binds to these IgE antibodies, triggering the cells to release a flood of chemicals like histamine and platelet-activating factor (PAF). Histamine causes itching and swelling, while PAF is linked to severe, life-threatening anaphylaxis. This reaction is rapid, often appearing within minutes, and can affect multiple body systems at once.

The Intolerance Pathway: A Digestive Disruption

Food intolerance is a digestive issue. It usually happens when your body lacks an enzyme to break down a food component, like lactase for milk sugar (lactose). Symptoms like bloating and cramps are uncomfortable but not life-threatening. They are typically dose-dependent (a small amount may be fine) and have a slower onset, appearing hours after eating.

Mistaking an allergy for an intolerance could be dangerous, while the reverse can lead to unnecessary dietary restrictions. For more detailed information, you can explore scientific research on food intolerance vs allergy.

Getting the right diagnosis is the foundation for getting your life back.

The Food Allergy Immune Response: How Your Body Mounts an Attack

Let's explore the intricate process that defines the food allergy immune response. By breaking it down, we can understand why our bodies react the way they do.

The First Mistake: How Sensitization and IgE Production Begin

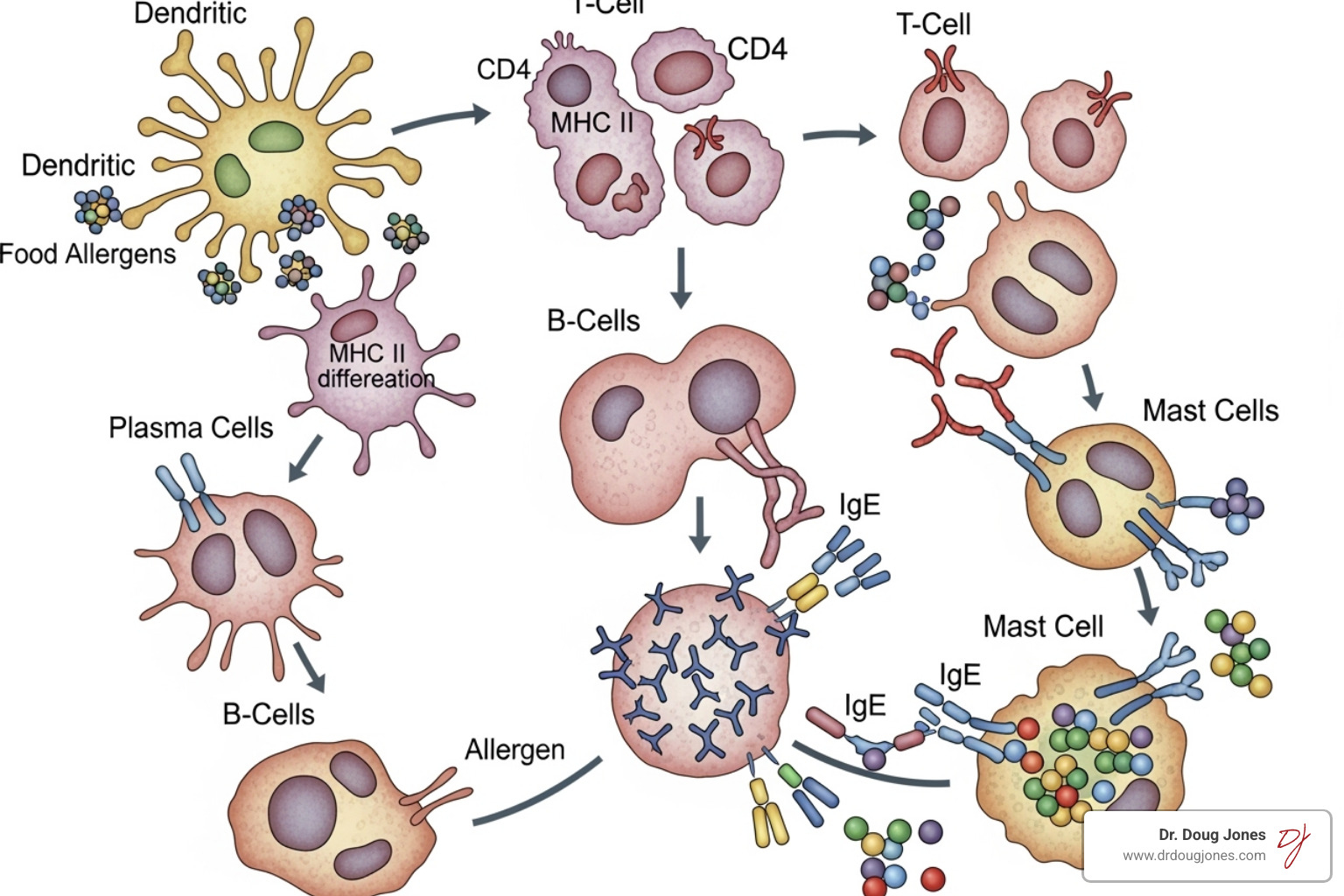

Every food allergy begins with sensitization. Immune system scouts, called dendritic cells, mistakenly identify a harmless food protein as a threat. They present it to T-helper 2 (Th2) cells, which orchestrate an allergic response.

These Th2 cells release chemical signals (cytokines) that command B-cells to produce large amounts of IgE antibodies specifically designed to target that food protein. These IgE antibodies then attach to mast cells and basophils, priming the body for a reaction.

The Reaction: Key Players and Chemicals

Once sensitized, re-exposure to the food allergen triggers a rapid attack. The allergen binds to the IgE on mast cells and basophils, causing them to degranulate—releasing a flood of inflammatory chemicals.

The main culprits are histamine, which causes hives, itching, and swelling, and platelet-activating factor (PAF), which is linked to severe anaphylaxis. Other immune cells like eosinophils can contribute to chronic inflammation, particularly in conditions like eosinophilic esophagitis.

This entire process is driven by a complex network of chemical messengers called cytokines that amplify the allergic response. Understanding these players helps explain why the food allergy immune response can be so powerful and persistent.

The Perfect Storm: Unpacking the Root Causes and Risk Factors

Developing a food allergy immune response is often the result of a perfect storm where genetics, environment, and timing collide. Scientists have finded that how and when you're first exposed to food proteins can determine whether your immune system sees them as friend or foe.

The Dual-Allergen Exposure Hypothesis

This theory explains how the route of exposure matters. Skin exposure, especially through damaged skin like eczema, can lead to sensitization and allergy. In contrast, early and consistent oral exposure (eating the food) promotes tolerance.

The groundbreaking LEAP trial findings proved this: high-risk infants who regularly ate peanut products had an 80% lower rate of peanut allergy. This highlights a critical window in infancy for teaching the immune system that food is a friend.

Skin Barrier Dysfunction and Eczema

Eczema (atopic dermatitis) creates a major risk factor for food allergies. Healthy skin is a strong barrier, but eczematous skin is "leaky," allowing food proteins from the environment (like peanut dust) to penetrate and trigger an immune alarm. Genetic factors, like mutations in the filaggrin gene which helps maintain the skin barrier, increase this risk.

The Gut-Immune Connection

Your gut microbiome—the trillions of bacteria in your digestive system—plays a vital role in immune health. A diverse, healthy microbiome helps your immune system develop oral tolerance, recognizing food as safe. It does this by supporting regulatory T cells (Tregs), the immune system's peacekeepers.

When the gut microbiome is out of balance (dysbiosis), Treg function can be impaired, increasing the risk of the immune system overreacting to food. Nurturing a healthy gut from early life is critical for preventing food allergies.

Diagnosing and Managing Food Allergies: From Testing to Daily Life

Navigating a food allergy diagnosis can be a complex puzzle. The food allergy immune response creates a surprisingly tricky diagnostic picture.

Why Sensitization Doesn't Always Equal Allergy

A common point of confusion is that you can test positive for a food allergy without being clinically allergic. Standard blood tests (serum specific IgE) and skin prick tests (SPT) measure sensitization—the presence of IgE antibodies. However, this doesn't guarantee you'll react when you eat the food. These tests are one piece to the puzzle, not the whole puzzle. They help provide clues to the diagnosis, but not necessarily the diagnosis.

The oral food challenge (OFC), where the food is eaten under medical supervision, remains the gold standard for a definitive diagnosis.

Advanced Diagnostics: A Deeper Look with Component Resolution

Component-Resolved Diagnostics (CRD) offers a more precise look. Instead of testing for a whole food, CRD tests for IgE against individual proteins within that food. This helps predict the severity and persistence of an allergy. For example, allergy to the peanut protein Ara h 2 is linked to more severe, persistent reactions. In contrast, allergy to certain heat-sensitive milk proteins may mean a person can tolerate baked milk products, even if they react to fresh milk.

Understanding Anaphylaxis and Taking Action

Anaphylaxis is the most severe food allergy immune response, a rapid, multi-system reaction that can be fatal. Symptoms can include hives and swelling, difficulty breathing, vomiting, dizziness, and a feeling of impending doom.

Epinephrine is the only first-line treatment for anaphylaxis and should be used without delay. Management involves:

- Strict Avoidance: Becoming an expert at reading food labels.

- Cross-Contact Prevention: Using separate utensils and surfaces to avoid contamination.

- Emergency Preparedness: Always carrying epinephrine autoinjectors and having a written emergency action plan.

The New Frontier: Prevention, Tolerance, and Advanced Treatments

We're in a revolution in how we treat the food allergy immune response. Instead of just hiding from allergens, we're learning how to retrain the immune system to recognize food as a friend.

Shifting Paradigms: The Power of Early Introduction

The biggest shift in allergy prevention is the strategy of early introduction. As shown by the LEAP trial, introducing allergenic foods like peanut and egg into an infant's diet between 4-6 months of age can significantly reduce the risk of developing allergies. This "window of opportunity" allows the immune system to learn tolerance.

Retraining the Immune System: Immunotherapy and Biologics

For those who already have allergies, treatments are available to retrain the immune system.

- Oral Immunotherapy (OIT) and SubLingual (SLIT) involves consuming via different routes (OIT vs SLIT) gradually increasing amounts of an allergen under medical supervision to build tolerance. With OIT, most patients can freely eat their allergenic foods without avoidance. With SLIT, the allergenic foods need to be avoided, still. Sometimes this can change with prolonged SLIT treatment.

- Biologics like omalizumab (Xolair) are injectable drugs that block IgE, preventing it from triggering allergic reactions. Allergenic foods must still be avoided. Sometimes it is used "off-label" in conjunction with OIT.

These therapies can reduce the risk of severe reactions from accidental exposure by changing the fundamental food allergy immune response.

How Food Processing Changes Allergenicity

How a food is prepared can change its ability to cause a reaction. Some allergenic proteins are heat-labile, meaning they break down with cooking. This is why many children with milk or egg allergies can safely eat these foods when they are extensively baked into a cake or muffin. Regularly eating these baked forms can even help some children outgrow their allergy faster by giving their immune system a safer way to practice tolerance.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Immune Response to Food

We've covered a lot about the food allergy immune response, but certain questions come up again and again. Here are the ones I hear most often.

What is the difference between IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated food allergies?

IgE-mediated allergies are the classic, rapid-onset type. They involve IgE antibodies, cause symptoms like hives and wheezing within minutes to two hours, and can lead to anaphylaxis.

Non-IgE-mediated food allergies are different. They are delayed, with symptoms appearing hours or days later. They involve different immune cells (like T-cells) and typically cause gastrointestinal issues, such as the severe vomiting in Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome (FPIES) or swallowing difficulties in Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE). Standard allergy tests are negative for these conditions.

Why do some people outgrow food allergies while others don't?

The ability to outgrow a food allergy depends on the food itself and the individual's immune system. Allergies to milk, egg, wheat, and soy are outgrown more often than allergies to peanuts, tree nuts, and shellfish.

As a child's immune system matures, it can develop tolerance by producing more protective antibodies (IgG4) and regulatory T-cells that suppress the allergic response. If the immune system remains highly reactive to stable proteins in the food, the allergy is more likely to persist.

When should I see an allergist or immunologist?

It's best to see a specialist sooner rather than later. You should seek an evaluation if:

- You consistently have symptoms within hours of eating a specific food.

- You experience any severe reaction, like difficulty breathing or widespread hives.

- You or your child has eczema, and you suspect food triggers.

- You are restricting your diet based on a suspected allergy without a formal diagnosis.

- You want guidance on early allergen introduction for an infant or are interested in immunotherapy.

Conclusion: Taking Control of Your Immune Health

We've journeyed through the complex world of the food allergy immune response, from the immune system's first mistake to the cascade of chemicals causing frightening symptoms. It's a clear demonstration of your immune system's power, sometimes misdirected.

The exciting news is that we are moving beyond simple avoidance. We are in a new era of understanding how to work with the immune system. We've seen how early introduction of foods can prevent allergies and how treatments like immunotherapy can retrain an allergic response. Even understanding how cooking can change a food's allergenicity opens up new possibilities.

At my practice, I believe understanding your unique immune patterns is the first step toward relief. My approach is not about quick fixes but about getting to the root cause and working with your body's capacity to heal. Your immune system learned these reactive patterns, and with the right guidance, it can learn new, tolerant ones. You don't have to live in a cycle of fear and avoidance.

If you or someone you love is struggling with food allergies or other complex immune issues, know that effective, personalized solutions are within reach. I'm here to guide you on this journey.